From Refuse to Royalty: The Birth of Oxtail

By Dianne Dunchie-Coley

Long before oxtail became a delicacy in Jamaica — before it appeared as Sunday dinner for the wealthy and in Kingston’s finest kitchens — it was nothing more than scraps. Back in the days of slavery, the masters took the best cuts of beef for themselves and tossed aside what they deemed useless: the head, the feet, the tripe, and the tail.

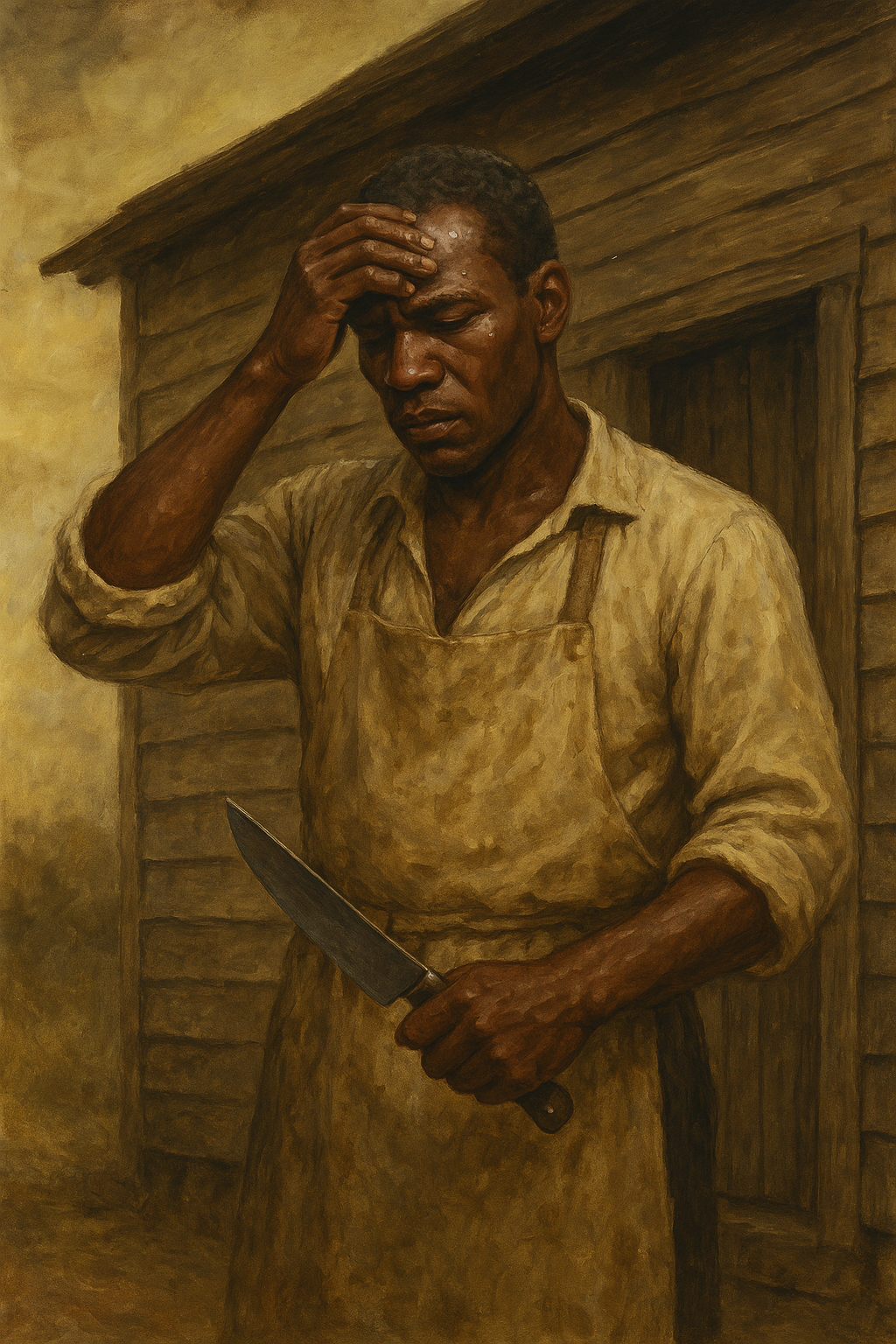

On Massa Jones’s plantation in St. Thomas, a man named Cudjoe worked as the butcher. Strong, quiet, and proud, Cudjoe had the steady hands of a man who understood both blade and bone. Each time he slaughtered a cow, Massa Jones promised him a small reward — some soap, a handful of cornmeal, maybe a cup of sugar.

But promises, like breeze through cane fields, have a way of shifting.

One scorching afternoon, after Cudjoe had finished dressing a fine cow, he wiped the sweat from his brow and waited for Massa’s word.

Massa Jones came striding down, fanning himself with a broad hat. “Eh, Cudjoe,” he barked, “you’ll get no corn or sugar today. Take what’s left of the beast — the head, the tail, the feet, and the innards. That’s payment enough for your kind.”

Cudjoe clenched his jaw, the insult cutting deep. Without a word, he scooped up the pile of refuse and flung it toward the big house kitchen, where Ma Tanty, the old cook, was tending her fire.

Now, Ma Tanty was no ordinary woman. Her hands carried the wisdom of generations, and her eyes could see hope where others saw only scraps. When Cudjoe’s bundle landed at her feet, she brushed off the dust, held up the tail, and laughed softly.

“So this is what him think fit fi we? Tail and tripe?” she said. “Well, we gon show him that even the refuse can rise up righteous.”

That night, she called the women from the quarters to gather round her pot.

“Come,” she said, her voice steady and warm, “is time we learn to make beauty from what dem call waste.”

Under the soft glow of moonlight, Ma Tanty guided them through the art of preparation. She showed how to scrape the tripe clean, removing every trace of impurity and fat, then wash it with lime and scald it in hot water. She demonstrated how to singe the cow’s head and feet over the open flame, and how to season the tail with thyme, pepper, and a touch of molasses, transforming refuse into a feast fit for kings. They chopped, stirred, and shared stories as the pots bubbled, the scent of survival drifting across the night air.

The tripe stew was hearty, the cow foot rich and sticky — but it was the oxtail that ruled as king. Slow-cooked until the meat slipped from the bone and the gravy turned thick and brown, it filled their bellies and lifted their spirits.

From that day on, each time Massa Jones butchered a cow and tossed the scraps toward the slaves, they accepted it with calm pride. The women would nod and say, “Give we the tail, sah — we know what to do wid it.”

For years, this ritual continued. What Massa meant as an insult became their secret strength. Out of survival, they created mastery; out of cruelty, they forged culture.

Then one afternoon, the air over the slave quarters shimmered with a smell so rich, so tempting, that even the birds seemed to linger mid-flight. The pot on Ma Tanty’s fire was bubbling low, releasing a sweet, smoky aroma that made the mouth water.

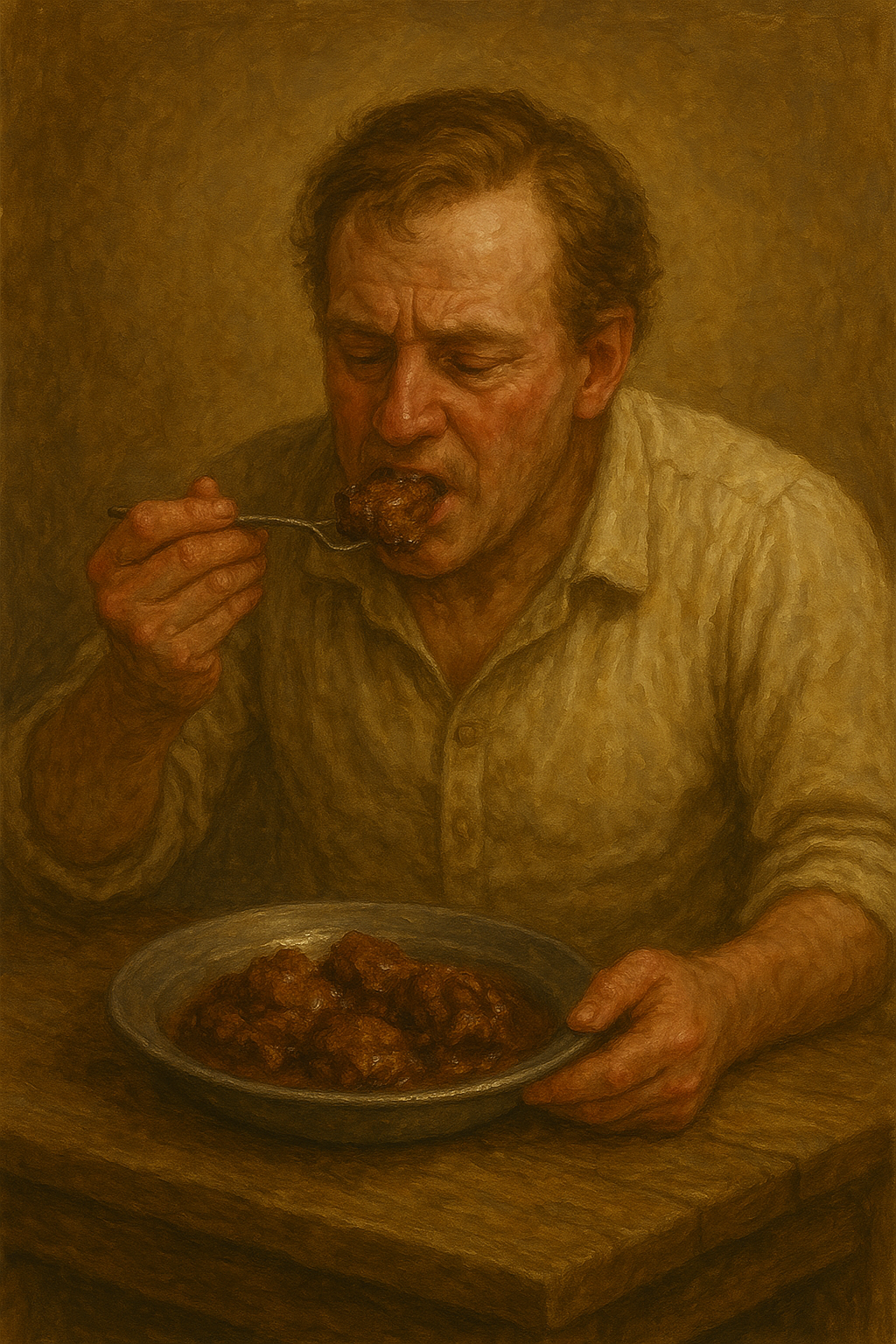

Massa Jones, strolling down from the big house, sniffed the air and stopped short. “What’s that smell?” he demanded. “Who cooking beef down here?”

Ma Tanty looked up from her pot, her eyes calm as river water. “No beef here, sah,” she said. “Just a bit of tail.”

“Tail?” he said, wrinkling his nose, yet unable to resist. “Let me taste it.”

She ladled a small portion into a tin bowl and handed it over. He tasted it once — then again — his eyes widening in disbelief.

“Why, this is finer than the roast I had for supper!” he exclaimed.

Ma Tanty smiled faintly. “Yes, sah. Seems the tail have a story to tell, if you let it simmer long enough.”

From that day, Massa demanded oxtail in his kitchen. But the people in the quarters knew the truth — that the dish belonged to them. It was their creation, born from fire, patience, and pride.

And so it was that what once was scorned became celebrated. The head, the foot, and the tripe each had their place, but it was the oxtail that ruled the pot — king of flavour, symbol of endurance, and proof that the spirit of a people cannot be starved.

Moral:

Even when the world throw you scraps, remember — you can still make a feast fit for kings.