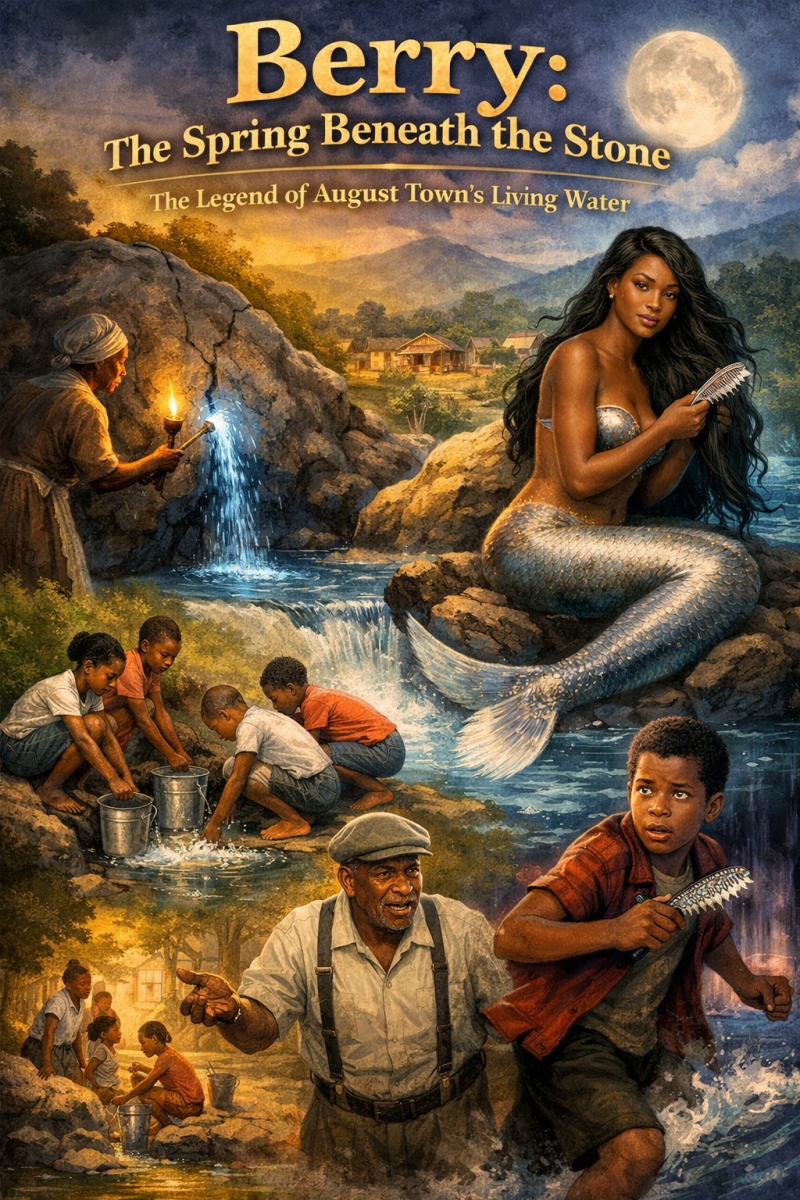

Berry: The Spring Beneath the Stone

By Dianne Dunchie -Coley

The Legend of August Town’s Living Water

Long before roads carved their way through August Town, before pipes carried water into homes, and long before children ran barefoot along the dusty lanes with buckets swinging at their sides, Berry was there.

August Town was a free village, established after the abolition of slavery in 1838 to house the freed men and women from the Mona Plantation and other plantations around the area. It was land claimed not by conquest, but by endurance—by people determined to build a life with their own hands, beneath their own sky.

And the elders say that Berry was not discovered. Berry revealed herself.

The spring burst forth from a stubborn seam in the face of a massive rock just along the bank of the Hope River. The rock was ancient, older than stories, older than memory. In the beginning, people passed it knowing only that the stone was cool to the touch, even under a blazing sun.

But one summer, a terrible drought swept through St Andrew.

The Hope River went dry, and its vastness was confined to a small path. Once, the river had run wide and deep—so wide that legend claims the gigantic stone behind August Town Primary School was part of the riverbed itself before the drought forced the river to change its course.

The drought made the Hope River a trickle, and the people who called August Town home had little to wash their clothes, feed their animals, or drink. Thirst made tempers short and children restless.

One night, under a swollen moon, an old newly freed woman named Ma Mimba heard singing near the river. Not just any tune—a sweet humming with no voice behind it, as if the water itself were dreaming aloud. She followed the sound with her bottle torch trembling in her hand.

When she reached the great rock, she saw a glow pulsing faintly from within its cracks—pale and blue like the breath of morning frost.

With one curious knock of her walking stick, the stone split—just slightly.

A trickle slipped out—clearer than glass, colder than night air.

Berry had begun to flow.

From that day forward, she never stopped.

Generations later, when summers scorched the earth and the taps in August Town fell silent, the children would be sent to Berry. Metal buckets scraped, plastic bottles clacked together like impatient teeth as they marched down the familiar track. The spring nestled between great boulders—like nature cupping her hands to offer a drink.

Some children dipped their faces straight in, tasting the mountain’s heart. The water was so cold it made their teeth chatter, even while the sun burned the back of their necks. To drink from Berry was to taste something older than concrete, politics, and the troubles of August Town life.

It tasted like hope.

But the elders always warned:

“Mind how yuh step, and mind what yuh say. Because River Mumma watching.”

They said River Mumma lived where Hope River deepened—half woman, half fish—her hair black as the midnight hillside, her tail silver like scales made of moonlight. She guarded Berry because Berry was life itself. Children claimed they saw her tail flick under the surface at dusk or heard a lullaby drifting against the sound of the current.

While most sightings were whispers and goosebumps, one story rang louder than all the rest.

A boy named Bedward, too bold for his own good, believed River Mumma was just an old folks’ tale. One evening, after hearing rumours of her diamond comb, he hid near Berry. And he saw her—resting against the rock, brushing her hair in the reflection of her own spring. When she slipped beneath the water, he grabbed the comb and ran.

That night, sleep abandoned him. When he shut his eyes, he saw water rising over his bed.

When he opened them, water still rushed in his ears. The river’s song followed him like a shadow with no source.

Three days without rest broke his pride. Trembling and pale, he returned the comb silently to the rock from which Berry flowed. A ripple answered him, soft and satisfied. And the spring continued its song.

Bedward became the loudest protector of Berry afterward, scolding children for littering and lecturing teenagers about respect.

Time changed August Town—roads paved, houses rose, children grew and migrated—but Berry still sang, cooling the air with her breath. Some say the spring flows because River Mumma keeps it clean, driving away those who treat the water carelessly. Others believe she watches over the community itself, ensuring that no shortage steals hope entirely.

Parents still tell their children:

“Leave the water clear as you found it.

Never disrespect the spring or its keeper.”

Because if Berry represents life, River Mumma represents memory—the connection between those who came, those who stayed, and those who still dream of the river on hot summer days.

And so the legend lives:

If you sit quietly beside the rock at dusk, listening to the rush of sweet, cold water, you might hear the faintest humming—a song older than fear, older than drought.

A reminder that Berry is not just a spring. Berry is a promise.

Protected by the Riva Mumma, for the children of August Town— past, present, and yet to come.